Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are periods of rapid physical and brain growth, and healthy nutrition in these years plays a vital role in long-term health. Research has shown that proper nutrition can support height and healthy weight gain, optimal brain development, and a stronger immune system. In contrast, unhealthy eating habits can lead to problems such as micronutrient deficiencies, growth disorders, or overweight and obesity.

According to official statistics, about one-third of Iranian students are affected by overweight or obesity; this is a warning sign for the future health of the younger generation. On the other hand, some teenagers may struggle with underweight or hidden malnutrition (such as iron-deficiency anemia), which can negatively affect their learning and growth.

In this article, based on the latest recommendations from reputable global sources (including the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the American Academy of Pediatrics), we provide a comprehensive nutrition guide for three age groups: 6–9 years, 10–12 years, and 13–15 years. The main focus is on the role of nutrition in physical growth, brain development, bone health, and preventing weight problems (obesity or underweight). We will also review daily needs for macronutrients and key micronutrients in each age group, give examples of daily meal plans, and correct common nutrition myths.

The role of nutrition in growth, brain development, bone health, and healthy weight

Healthy nutrition is a balanced combination of the main food groups (complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, vegetables and fruits, low-fat dairy, and healthy fats), each of which is essential for a specific aspect of teen health. Below we look at four key dimensions of how nutrition affects adolescent health.

1. Linear growth and physical development

Adequate energy (calories) and protein intake is essential for increasing height and maintaining a healthy weight. During growth spurts (for example around ages 9 to 14), children’s appetites usually increase significantly to cover the higher caloric and protein needs of growth. A lack of calories or protein at these ages can lead to slower height growth or extreme thinness, while excessive intake of high-calorie, low-nutrient foods increases the risk of excessive weight gain.

Therefore, balancing energy intake and expenditure (through physical activity) is crucial for maintaining a healthy weight. Adolescence is the time when eating patterns and lifestyle habits are formed for later life; if overeating, constant snacking on junk food, and physical inactivity become the norm in this period, the risk of obesity in adulthood increases.

2. Brain development and academic performance

Teen brains need a steady supply of nutrients to develop properly. Omega-3 fatty acids (from sources like fish), iron, zinc, and B vitamins are critical for brain growth and function.

- Iron is important for the formation of red blood cells and transporting oxygen to the brain; deficiency can cause poor concentration and academic decline.

- Zinc and iodine are important for memory, attention, and cognitive performance.

- B vitamins (especially B₆, B₉, and B₁₂) are involved in brain energy metabolism and the production of neurotransmitters.

A balanced diet containing adequate protein, whole grains, leafy green vegetables, and nuts can provide these key micronutrients. Studies show that children with healthier diets tend to perform better in school and have better memory.

(Concept image: a teenager studying at a desk with a plate of nuts, fruit, vegetables, and fish beside them; soft 3D style with pastel colors.)

3. Bone and dental health

Middle childhood and early adolescence are a golden window for building bone mass; by around age 20, most of a person’s peak bone mass has formed. Calcium and vitamin D are the two key factors for strong bones and teeth.

- Children aged 6–8 years need about 1,000 mg of calcium and 600 IU of vitamin D per day.

- From around age 9 onward, calcium needs increase to about 1,300 mg per day.

Rich sources of calcium include dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese), leafy greens such as kale and cabbage, and almonds. Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin by sunlight exposure and is also found in foods like fatty fish (salmon, sardines) and egg yolks.

Beyond nutrition, regular physical activity and sports (especially weight-bearing activities like running, jumping, football, basketball) work together with good nutrition to increase bone density in teenagers.

4. Preventing obesity and underweight

Childhood and adolescence are the ages when healthy eating patterns are established. Obesity at these ages can pave the way for serious health issues later in life. Teen obesity is linked to increased risk of:

- early puberty

- type 2 diabetes

- high blood pressure and cardiovascular problems

- low self-esteem and psychological issues

On the other hand, underweight and malnutrition can cause a weakened immune system, fatigue, stunted growth, and poor school performance.

The basic strategy for prevention is to provide a balanced diet and control portion sizes, meaning:

- plenty of fruits and vegetables (at least 5 servings per day)

- lean protein sources (white meat, legumes, eggs, nuts)

- low-fat, calcium-rich dairy

- limiting sugar and unhealthy fats

The World Health Organization recommends that added sugars should make up less than 10% of daily calories in children (around 5% is ideal), since high sugar intake and sugary drinks are linked with overweight and obesity. Intake of saturated and trans fats (solid oils, fast food, packaged snacks) should also be minimized, and most fats should come from healthy unsaturated sources (liquid vegetable oils, nuts, fish).

Alongside nutrition, at least 60 minutes of physical activity per day (active play, sports, cycling, brisk walking) is recommended to maintain a healthy weight and prevent obesity.

Nutritional needs of children aged 6–9 years

In the early primary school years (around 6 to 9 years), children’s growth is slightly slower than in earlier years but remains steady. Children in this age group usually have a fairly stable appetite, though they may experience a growth spurt around ages 8–9 with a noticeable increase in hunger. The focus of nutrition at this age is to provide enough energy for growth and play, while also teaching healthy eating habits.

1. Daily energy and macronutrient needs

A 6–9-year-old child, depending on sex and activity level, needs about 1,400 to 1,800 kilocalories per day. These calories should come from varied sources, roughly:

- about 50–60% from complex carbohydrates (whole-grain bread and cereals, brown rice, whole-wheat pasta, etc.)

- about 25–30% from healthy fats

- and around 15% from lean protein

Protein needs in this age group are about 19–20 grams per day (roughly equal to about 1.5 servings of meat or egg).

2. Daily requirements for key vitamins and minerals (6–9 years)

| Nutrient | Recommended daily intake (6–9 years) |

|---|---|

| Calories | About 1,400–1,600 kcal |

| Protein | ~20 g (minimum) |

| Vitamin A | 400–500 µg RAE |

| Vitamin D | 600 IU (15 µg) |

| Vitamin C | 25 mg per day |

| B vitamins | Varies (e.g., B₁₂ around 1.2 µg) |

| Calcium | 1,000 mg |

| Iron | 10 mg per day |

| Zinc | 5 mg per day |

Note: Around age 9, the requirements for some micronutrients (like iron and calcium) change; for example, recommended iron decreases to 8 mg and calcium increases to 1,300 mg. The table above presents approximate values for the middle of this age range.

At this age, getting micronutrients from a diverse diet is very important. For example:

- Vitamin A, essential for growth and eye health, is found in foods like carrots, sweet potatoes, egg yolks, and liver.

- Vitamin D is necessary for calcium absorption and bone growth; in addition to sunlight, it is found in fatty fish and fortified dairy products.

- Iron is crucial for preventing anemia and supporting learning, and can be obtained from lean red meat, poultry, fish, legumes (such as lentils and beans), dried fruits, and spinach.

Combining plant-based iron sources with vitamin C (for example, lentil soup with fresh lemon juice) improves iron absorption.

3. Reviewing eating habits

Parents should help establish healthy eating habits during this stage. For example:

- reducing intake of soda and sugary snacks and replacing them with water and healthy snacks (fresh fruit, yogurt, nuts and dried fruit)

- emphasizing breakfast as a very important meal; skipping breakfast can lead to fatigue, poor concentration, and overeating later in the day.

A 6–9-year-old typically needs three main meals and two light snacks per day.

4. Sample daily meal plan for an 8-year-old child

- Breakfast: One glass of low-fat fortified milk, one boiled egg, some whole-grain traditional bread (like sangak or barbari) with cheese and walnuts, plus one cucumber and a tomato.

- Morning snack: One apple or banana with a small handful of almonds or raisins.

- Lunch: Stew with meat and split peas (e.g., a traditional lentil or meat stew) using lean red meat (about the size of the child’s palm), lentils and potatoes, served with semi-wholegrain rice (about 1½ ladles) and a side salad (lettuce, tomato, cucumber, carrot) with lemon juice. Low-fat yogurt as dessert.

- Afternoon snack: One glass of homemade banana milk (low-fat milk + one small banana) or a small whole-grain sandwich with peanut butter and honey.

- Dinner: A bowl of noodle soup or chicken and vegetable soup (with carrot, potato, peas), served with half a whole-grain flatbread.

Nutritional needs of children aged 10–12 years

The ages 10 to 12 (late primary school and the beginning of middle school) correspond to the pre-puberty stage. Hormonal changes begin, and linear growth gradually speeds up, especially in girls around age 10 and in boys around age 12, when they start their adolescent growth spurt. Appetite may increase, and nutritional needs rise as they get closer to puberty.

1. Daily energy and macronutrient needs

A 10–12-year-old child typically needs about 1,800 to 2,200 kilocalories per day. Girls often experience an appetite increase slightly earlier than boys at the onset of puberty, but overall, before full puberty there is no major difference in energy requirements between boys and girls in this group.

It is still recommended that:

- about 50% of calories come from complex carbohydrates

- about 30% from healthy fats

- and 15–20% from protein

Protein needs in this age range are about 34 grams per day, which can be met through sources like white meat (chicken and fish), eggs, legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans), and nuts. Adequate fiber intake (around 22–25 g per day) from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is important for good digestion and satiety.

2. Daily requirements for key vitamins and minerals (10–12 years)

| Nutrient | Recommended daily intake (10–12 years) |

|---|---|

| Calories | Around 2,000 kcal |

| Protein | ~34 g per day |

| Vitamin A | 600 µg RAE |

| Vitamin D | 600 IU (15 µg) |

| Vitamin C | 45 mg per day |

| B vitamins | Varies (e.g., B₁₂ about 1.8 µg) |

| Calcium | 1,300 mg per day |

| Iron | 8 mg per day |

| Zinc | 8 mg per day |

Note: At the threshold of puberty, especially in girls, iron needs become more important with the onset of menstruation around age 12. Although the RDA for iron in ages 9–13 is 8 mg, parents should ensure that girls in this age range have adequate iron stores to avoid anemia at the beginning of puberty. Eating iron-rich foods together with vitamin C and, if needed, consulting a doctor about iron supplements can be helpful.

In this age group, adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is still a top priority, as early puberty is a critical time for bone mass gain. Children aged 10–12 are generally advised to consume about 3 servings of dairy per day (e.g., three glasses of milk or equivalent yogurt/cheese) to reach 1,300 mg of calcium.

High-quality protein sources (lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, soy) should be included in the diet to meet protein needs and contribute to zinc and iron intake.

3. Appetite changes and eating patterns

As children approach adolescence, they gain more independence in food choices (buying from the school cafeteria or eating at friends’ houses). Teaching healthy food selection skills at this age is very important.

Parents can encourage children to choose healthier snacks instead of packaged sugary and fatty foods—for example fruit, unsalted nuts, homemade healthy sandwiches, or low-fat fruit yogurt. Drinking water instead of soda and commercial juices, and limiting fast food to at most once or twice a month, are good habits to establish.

4. Sample daily meal plan for an 11-year-old child

- Breakfast: A bowl of fortified whole-grain breakfast cereal with one glass of low-fat milk, plus one banana and 5 almonds.

- Snack: A small bowl of low-fat Greek yogurt with half a cup of chopped strawberries, or one orange.

- Lunch: A homemade chicken and cheese sandwich: whole-grain bread, 90 g grilled chicken, one slice of low-fat cheese, lettuce, and tomato. Served with sliced carrot and cucumber and hummus as a dip, plus a glass of low-salt yogurt drink (doogh or kefir).

- Afternoon snack: A handful of mixed unsalted nuts (pistachios, almonds, walnuts) and raisins + one apple.

- Dinner: Whole-wheat pasta (about 1.5 cups cooked) with homemade meat and vegetable sauce (lean ground beef, mushrooms, bell pepper, grated carrot) topped with a little Parmesan. Side salad (lettuce and wheat sprouts) with olive oil and balsamic vinegar.

Nutritional needs of teenagers aged 13–15 years

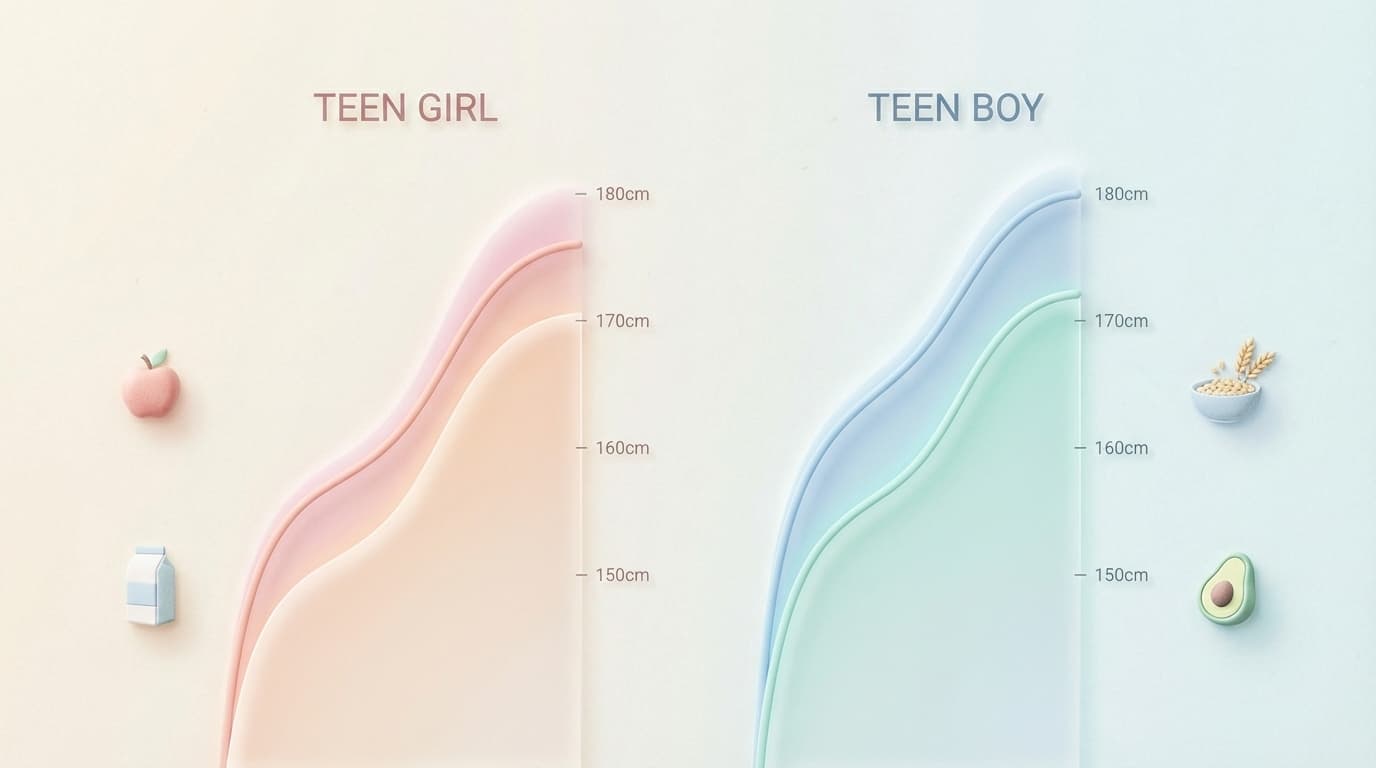

Early adolescence (13 to 15 years) is marked by the pubertal growth spurt. At this age, most girls have started menstruating and boys are experiencing rapid increases in height and weight. Nutritional needs in this group are significantly higher than in younger children, and sex differences become more pronounced.

Many teenagers reach their peak appetite around age 14, and their bodies require plenty of energy and nutrients to support rapid growth.

1. Daily energy and macronutrient needs

- A 13–15-year-old boy typically needs about 2,400 to 2,800 kilocalories per day.

- Girls of the same age usually need about 2,000 to 2,200 kilocalories.

These values vary according to growth rate and activity level; tall or very active boys may need 3,000 calories or more.

The macronutrient distribution should still be balanced:

- about half of the energy from complex carbohydrates

- about one-quarter from healthy fats

- and about one-quarter from protein

Protein needs in this age range are around 52 g per day for boys and 46 g per day for girls, which roughly corresponds to two servings of meat or fish plus two servings of dairy per day.

A variety of protein sources (lean red meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and nuts) should be part of a teenager’s diet to cover the increased protein needs for muscle growth.

2. Daily requirements for key vitamins and minerals (13–15 years)

| Nutrient | Boys 13–15 years | Girls 13–15 years |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | ~2,500 (about 2,000–3,000 depending on activity) | ~2,200 (about 1,800–2,400 depending on activity) |

| Protein | 52 g per day | 46 g per day |

| Vitamin A | 900 µg RAE | 700 µg RAE |

| Vitamin D | 600 IU (15 µg) | 600 IU (15 µg) |

| Vitamin C | 75 mg | 65 mg |

| B vitamins | B₆ about 1.3 mg; B₁₂ about 2.4 µg | B₆ about 1.2 mg; B₁₂ about 2.4 µg |

| Calcium | 1,300 mg | 1,300 mg |

| Iron | 11 mg | 15 mg |

| Zinc | 11 mg | 9 mg |

In early adolescence, girls’ iron needs rise to about 15 mg per day due to menstrual blood loss, while boys’ needs are about 11 mg. Iron deficiency in teenage girls can lead to anemia, fatigue, and reduced concentration.

Therefore, eating iron-rich foods (lean red meat, liver, legumes, dark leafy greens, iron-fortified cereals) with sufficient vitamin C to enhance absorption is strongly recommended. If necessary and as prescribed by a doctor, iron supplements or multivitamins with iron may be appropriate for girls in this age group.

Calcium and vitamin D remain essential for both sexes as bone density continues to increase. Teenagers aged 13–15 should have three servings of dairy or equivalent calcium sources (e.g., calcium-fortified soy milk) daily to reach 1,300 mg of calcium.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, many teenagers do not meet the recommended intake for calcium, iron, zinc, and vitamin D, largely because healthy foods are replaced by processed snacks that are low in micronutrients.

3. Behavioral changes around food during adolescence

At this age, teenagers have more independence in food choices and spend more time outside the home. The tendency to eat ready-made foods (fast food, packaged snacks, sugary drinks) often increases.

Parents should, while maintaining a good relationship and avoiding excessive strictness, encourage healthier choices. For example:

- instead of giving cash that will probably be spent on fast food, provide ingredients for a healthy sandwich

- read and discuss nutrition labels with the teen, focusing on high sugar, unhealthy fat, and salt content

- teach basic cooking skills and involve the teenager in preparing meals; this often increases their interest in healthy homemade food

4. Sample daily meal plan for a 14-year-old teenager

- Breakfast: Vegetable omelet (2 eggs + mushrooms, bell pepper, spinach) cooked in a small amount of olive oil, with 1–2 slices of whole-grain toast and a glass of low-fat milk.

- School snack: A small whole-grain sandwich with peanut butter and honey, one banana, and a bottle of water.

- Lunch: Homemade “doner-style” wrap (turkey or lean beef strips grilled with a little oil and spices) served in whole-wheat pita bread with Shirazi salad (tomato, cucumber, onion, mint) and yogurt.

- Afternoon snack: Homemade fruit smoothie (e.g., yogurt, strawberries, banana, ice) or a small bowl of mixed nuts plus slices of watermelon or melon.

- Dinner: Grilled salmon (about 150 g) or trout, with one medium baked potato and steamed vegetables (broccoli, carrot, green beans) drizzled with a little olive oil and lemon juice, plus a small lettuce and tomato salad.

Common myths about teen nutrition

In everyday culture and among some families, beliefs about teen eating habits circulate that are not necessarily scientifically sound. Below are some common myths in Iran, along with evidence-based clarifications.

1. “Cutting all fat from a teen’s diet leads to health and a better body shape.”

This is incorrect. While reducing unhealthy fats (saturated and trans fats) is important, completely eliminating fat from the diet can harm a teenager’s health.

Healthy fats (unsaturated fats) are essential for:

- brain development

- absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K)

- hormone production

According to the American Heart Association and other scientific bodies, about 25–35% of children’s and teenagers’ daily calories should come from healthy fats.

So instead of cutting all fat, we should include healthy sources (liquid vegetable oils such as olive and canola oil, fish, nuts, avocados) and limit foods high in saturated fat (fast food, butter, chips).

2. “Teenagers who are growing should eat as much as possible; feeling completely full means they are well nourished.”

This is also not accurate. It’s true that teens’ energy and nutrient needs are high, but this does not mean overeating or eating beyond comfortable fullness. Children and teens normally have an internal appetite regulation mechanism, and they shouldn’t be forced to eat more when they feel full.

Pressuring them to finish large portions can build a habit of overeating and contribute to obesity. It’s better to:

- teach teenagers to listen to their body’s hunger and fullness signals

- let them adjust portion sizes themselves (with guidance from parents)

Instead of insisting on large quantities, parents can increase the quality and variety of healthy foods so that teens get nutrient-dense options in the amounts their bodies actually need.

3. “Skipping dinner and snacking instead is a good way to control weight or provide energy for teens.”

This approach is wrong and may even be harmful. Dinner is one of the major meals and can cover about one-third of daily needs.

Studies show that teenagers who skip main meals, especially dinner, and replace them with high-calorie snacks at night are more likely to develop overweight or obesity. Skipping dinner can:

- reduce intake of essential nutrients (vitamins and minerals)

- increase the consumption of high-calorie, low-nutrient snacks (chips, sweets, soda)

This pattern not only promotes weight gain but can also lead to poor sleep quality and reduced academic performance due to night-time hunger or overeating.

Instead of skipping dinner, a light and balanced evening meal (such as soup, a salad with lean protein, a vegetable omelet, or light stew) should be eaten in the early evening. If a teen feels hungry later at night, a small snack like a glass of warm milk or a piece of fresh fruit is enough.

Conclusion and final recommendations

Healthy nutrition during childhood and adolescence lays the foundation for your child’s future health and success. By providing balanced amounts of energy, macronutrients, and essential micronutrients, teenagers can:

- reach optimal height and weight,

- enjoy a sharp, active mind,

- build strong bones,

- and prevent problems such as obesity, anemia, and more.

Parents play a key role in shaping healthy eating habits. Try to:

- be a good role model in your own eating

- keep a variety of nutritious foods available at home

- encourage regular physical activity

If you are concerned about your teenager’s growth or nutritional status, be sure to consult a pediatrician or dietitian. With awareness and attention to the age-specific nutritional needs of each stage, you can help your child go through childhood and adolescence with health, energy, and confidence, and build a solid foundation for a healthy life.

OsifyAI

OsifyAI